Early voting starts Monday for the December 8 District 2 Dallas school board runoff, a richly funded nip and tuck between incumbent Dustin Marshall, a Preston Hollow guy, and maverick challenger Nancy Rodriguez of East Dallas. These elections are supposed to be non-partisan.

Forget that. It’s partisan up one side and down the other. But just try to figure out who’s really who and what’s really what, I dare you.

Marshall, who has been a champion of the successful school reforms put in place by former superintendent Mike Miles, is definitely a Republican, but he doesn’t advertise it. Rodriguez advertises the heck out of being a Democrat, but I’m not sure she is, depending on what you mean by Democrat.

I looked up their voting records. The usual way to determine a person’s party affiliation is by which primaries they have voted in, a matter of public record. Marshall’s primary voting record is all Republican. But so is Rodriguez’s.

To be fair, Rodriguez has voted in only one primary in Texas – the Republican primary in 2016. “I did vote in the Republican primary,” she says. “I thought it was important to choose the Republican candidate, especially given who we wound up with.”

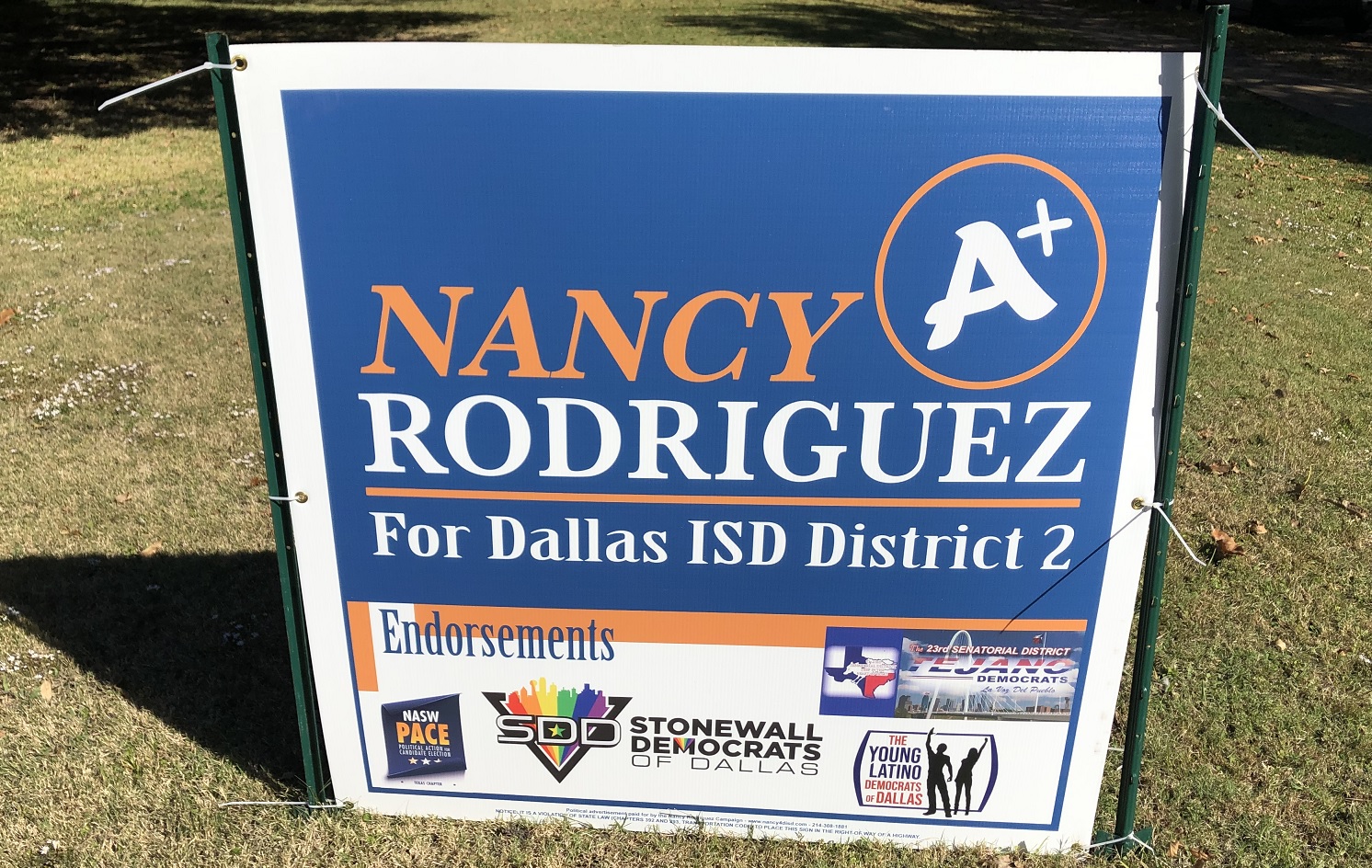

Her advertising in this officially non-partisan race is aggressively Democratic, showing off a roster of endorsements from Democratic political organizations. She and her husband, retired lawyer Barry Jacobs, promote her candidacy online as a crusade to “take this seat back from the millionaire and billionaire Republicans.” (That would be Marshall, who owns a freight and logistics company).

Marshall is interesting on this score as well. Most of his endorsers are Republicans, but he appears to be endorsed also by far more Democratic elected officials than Rodriguez – Dallas County Judge Clay Jenkins, Democratic State Rep. Rafael Anchia, former Dallas school board president Miguel Solis, former Dallas Mayor Mike Rawlings, and former Dallas Mayor and Obama cabinet member Ron Kirk. For a Republican, his list looks suspiciously Democrat. For some serious East Dallas cred, he also won an endorsement from former (nonpartisan) Dallas City Council Member Angela Hunt.

Some small irony may be found in Jacobs’ animus for Republicans, given that his own voting record is at least as Republican as Marshall’s and his history of political contributions maybe even more so. According to the political reporting website “Open Secrets.org,” Jacobs contributed money to the presidential campaigns of Rudolph Giuliani in 2007, Herman Cain in 2011 and Ted Cruz in 2016 (twice). Rodriguez tells me that, “We have always been a bipartisan family,” and she quite properly says she should not be judged by her husband’s political contributions. Her name does not show up as having made any reportable contributions.

But then, part of the puzzle here is that the ostensibly hyper-partisan nature of the race isn’t really what it’s about anyway.

For that part – what it is, what it isn’t – I turned to my distinguished and estimable neighbor, former State Rep. and former Dallas school trustee Harryette Ehrhardt, a stalwart of the Texas Democratic Party and, frankly, the smartest Democrat I know. Ehrhardt started off by decorously and diplomatically telling me to take my questions about Rodriguez’s true party affiliation and put them where the sun don’t shine.

“I have not talked to her about her party affiliation,” Ehrhardt says, “but I did talk about the things that I believe are important, and [her positions on those issues] more nearly reflect the policies of the Democratic Party. To that extent, you don’t have to say, ‘Are you a Democrat?’ You can say, ‘How fond are you of Trump?’ and you know.”

Why is being a Democrat or a Republican so important, if this is a non-partisan school board race? There are several reasons, some of which are fairly transparent, others a bit more subterranean. The obvious part is that the district Marshall and Rodriguez fight for on Dec. 8 is a crazy doughnut around the affluent Park Cities, with a heavily Republican electorate on Marshall’s western end in Preston Hollow balanced against what is believed to be a majority Democratic demographic on Rodriguez’s East Dallas end.

Rodriguez beat Marshall narrowly in the general election, but neither got enough votes to win outright. Hence.

Marshall has been in a couple of these squeakers before. Greatly advantaged by money, he has been able to extract victory from the jaws of defeat in previous elections by churning up greater turnout on the Preston Hollow side. Rodriguez’s path to victory in the upcoming runoff depends entirely on what turnout she can muster at the more Democratic end of the district. And in December, she will no longer have the advantage of Trump to hate at the top.

To beat Marshall in this runoff, you want to be a big-time Democrat or at least look like one. So that’s the easy stuff. But what’s beneath the surface?

For that, I depend again on my neighbor. “The things that are important to me,” Ehrhardt tells me, “are her relationships with teachers.”

What about them?

“I do not believe that the board should be in an adversarial position with their teachers,” she says. “She [Rodriguez] has the support of both teacher groups [asterisk], and that is important to me.”

The asterisk: we can argue all day about the meaning of the phrase “teacher groups,” but it’s unions. Texas has weird anti-union laws, especially for public employees, so collective bargaining organizations call themselves by a funky vocabulary of euphemisms, all of which makes a former union guy like me sad. But NEA Dallas and Texas Alliance-AFT, both of which have endorsed Rodriguez, are either unions or the next best thing in Texas.

They hate the Mike Miles school reforms. The reforms in Dallas did away with the centerpiece of what any decent union defends — seniority pay. The argument for doing it was and is that seniority pay is the enemy of racial equity. And here is where Democrats and Republicans and even some very smart people trip over their own tails.

The Miles reforms, which have been stunningly successful by any objective measure, turn on a set of ideas. First, if kids in a certain school do badly on reading and math achievement tests and if kids at that school have always done badly, it’s the school that has a responsibility to change, not the kids.

Second, the way to change the school is to send in the cavalry. Exemplified by the district’s highly successful ACE schools program, this means committing the very best school administrators and the most effective teachers. But how do you know who they are? And how do you get them to go?

One of Miles’ keystone reforms is an evaluative system that uses an array of factors, among which are student test scores, to rank teacher effectiveness. Another key is incentive pay. If an effective teacher volunteers to teach in a school with greatest need, that teacher gets more money.

In this way, the reforms steer the best and most effective adults into schools where children’s needs are greatest. That is how so-called “merit pay,” under the reform system, is bonded at the hip with racial equity.

And all of that, according to Ehrhardt, is a bunch of bloodless Republican baloney that only airheads like me believe. “I think it pits teachers against each other as if you were seeing who could sell the most cars during a car sell-a-thon,” she says, with feeling. “Is that really the way we get the best education for our children? Our children do better when teachers work with each other than they do when we say, ‘You’re going to get paid when you prove you can do better than the other second-grade teachers.’”

Eharhardt and Rodriquez are in lockstep in their antipathy for what they call “standardized tests” — another tell for where they’re coming from. For the last several years, since the advent of contemporary school reform, the unions have made “standardized tests” their primary bogeyman, making me wonder if the problem could be solved by using only “un-standardized” tests (no idea what that would be, really). Some screeds against standardized tests are so floridly conspiratorial, they make me imagine a secret world where standardized test oligarchs commit test abuse on private Caribbean islands.

That’s not Ehrhardt. She’s too smart. In fact, she expresses much of the same rigorously intellectual liberal values I grew up with. Boil it down, the idea is that the only way to help poor children is to eradicate poverty.

I’ve been waiting on that one to get done my whole life. No luck so far, in spite of an entire war on poverty when I was younger. In the meantime, the public school system that was in place here before the reforms was what child advocacy experts called the “school to prison pipeline.”

Any serious effort to improve a school to prison pipeline seems worth trying. Given the documented success of the current Dallas reforms, dialing back on them now, as Rodriguez proposes, feels strange, no matter how happy it may make the unions.

I say all of that to Ehrhardt, because I know it will light her up. She does not disappoint.

“The root problem of why kids go to prison,” she says, “is not based on the second-grade reading test. It’s based on whether there are jobs in that area. It’s based on whether they have decent housing, whether [the parents’] pain will allow them to work two full-time jobs and still support their children, whether they spend two hours going to work in the morning and two hours coming back, which means that they leave for work before the kid even gets up.

“That’s the problem,” she says. “The problem is not whether kids are passing standardized tests.”

Rodriguez brought up another argument against the reforms that has been aimed at me personally on social media by her husband, the Republican moneybags (oh, just kidding). That argument is that one nationally normed test, the National Assessment of Educational Progress, shows far less progress in Dallas schools than the reformers claim.

It’s a legitimate criticism. I ran it by Marshall. He sent me a bunch of statistical analyses to prove it’s not true. I will take up all of that in a future post on this topic. You still here?